TimeLine South’s RECIDIVISM :: Explore

On this page, learn more about the TimeLine South 2022 Ensemble and read further information and context around their world premiere play Recidivism: The Beginning of a Never Ending Cycle.

MEET THE ENSEMBLE

Dalencia Brown

Dalencia Brown

I’m Dalencia (she/they), the Artistic Fellow for TimeLine South this year. This is my 3rd year being a part of TimeLine. I’m an aspiring poet and actor; my favorite hobbies are cooking and performing of any kind. I play AJ, a young child learning to accept themselves while navigating a world that doesn’t quite fit. I’m honored to be trusted with telling this important story. Children all over the world should be allowed freedom to express themselves and learn without worrying about the many “isms” of the world. I hope to inspire change with this play!

Lamont Coffee

Lamont Coffee

Coffee is a mind oriented person with a passion for learning and creativity. Playing the role of Sam this year is kinda out of his character but he wishes that his character and this story leaves a lasting impact on those who listen in.

Talitha Cunninghamf

Talitha’s bio is coming soon!

Aja Dorsey

Aja Dorsey

Playing the role of Shalonder is Aja Dorsey. She is a rising Freshman at Muchin College Prep. A fun fact about her is that she is known as a class clown similar to her character Shalonder.

Trinity Evans

Trinity Evans

Hi! I’m Trinity Evans, and I’m playing Emery in this play. This is my 2nd show with TimeLine South. I enjoy singing, dancing, and acting. I loved working with everyone and finding a way to portray this sensitive topic. I hope to see everyone again next summer.

Kimora Gearring

Playing the role of Mike Is Kimora Gearring. She is an incoming freshman at Morgan Park. Besides acting, Kimora has many other talents including drawing and basketball. This play is Important to her because it relates to her because of what she experienced.

Yahir Lira

Yahir Lira

HELLO EVERYONE!!!!!!!! I am Yahir and I am playing the role of Jimmy. This is my first time in TimeLine and I hope y’all enjoy this show. I like to draw, cook, act, and maybe sing. I’m really glad I get to be in this play with these wonderful people I get to work with.

Shayla Miller

Shayla Miller

Playing the role of Destiny is Shayla Miller. She is an incoming freshman at Johnson College Prep. She is excited to be making her acting debut tonight.This topic is important to me because our voices should be heard.

Makahah Simpson

Makahah Simpson

Hey! I’m Makalah Simpson. I’ll be playing the role of Angeni in the play, and I’m so excited to be included! I’m a rising senior at Thornton Fractional South, and my hobbies include singing and creating various forms of visual arts. My passion is aiding in the restoration of endangered animals and environmental protection, and I use theatre as a creative outlet to escape from a busy school life!

SUPPORT NOT COURT

What is the Prison Industrial Complex?

As explained by abolitionist organization Critical Resistance, “the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” By naming the PIC, we identify the expansive network of people and parties with vested interests in mass incarceration and uncover how this network functions to fill prisons and support mass incarceration.

Racial Disparities in Mass Incarceration

Legal scholar Michelle Alexander writes that mass incarceration is the United States’ “new Jim Crow.” Black people and other people of color are incarcerated at much higher rates than their white counterparts. Recent evidence also suggests that although the population of incarcerated people has decreased since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, racial disparities have widened: the incarceration rates of Black and Latino/a people have decreased more slowly than the rate for white people.

4x

Black people are incarcerated in state prisons at a rate nearly 4x that of white people

1 in 41

Black adults in the U.S. are incarcerated in state prisons

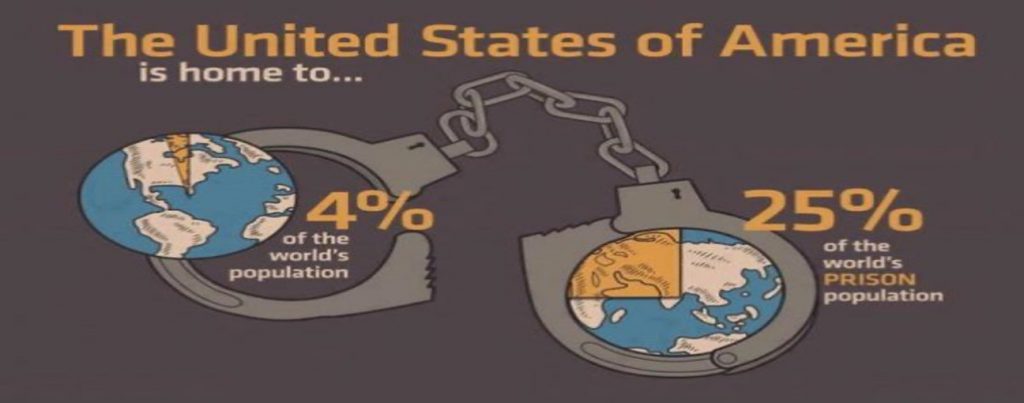

Mass Incarceration in Numbers

The United States is the epicenter of mass incarceration. From its origins in slavery to the rise of the War on Drugs in the late-twentieth century, the United States has incarcerated millions, disproportionately targeting and incarcerating Black people, other people of color, and people living in poverty.

4%

The U.S. is home to 4 percent of the world’s population

16%

Yet the U.S. is home to nearly 16% of all incarcerated people in the world

The number of people incarcerated in jails in prisons has increased dramatically since 1980: approximately two million people are incarcerated today, compared to roughly 500,000 in 1980. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people incarcerated began to decrease, though local jails have since seen a slight uptick in incarceration.

The impact and cost of Mass Incarceration

Proponents of the incarceration state often claim that putting people behind bars is the surest way to decrease crime. However, decades of research proves otherwise. A 2015 study concluded that since 2010, “the increased use of incarceration accounted for nearly zero percent of the overall reduction in crime.” At least 19 states have decreased both their crime rate and incarceration rate since 2000, from Alaska and Texas to Mississippi, New York, and Vermont.

Incarceration is also expensive. Vera’s research has shown that the United States spent roughly $33 billion on incarceration in 2000 for essentially the same level of public safety it achieved in 1975 for $7.4 billion—nearly a quarter of the cost.

Mass incarceration has steadily increased over the last four decades, disproportionately targeting Black people, other people of color, and those living in poverty, with few benefits and scores of harms.

Keep Youth Out of Adult Courts, Jails, and Prisons

Currently an estimated 250,000 youth are tried, sentenced, or incarcerated as adults every year across the United States. During the 1990s—the era when many of our most punitive criminal justice policies were developed—49 states altered their laws to increase the number of minors being tried as adults. On any given day, 10,000 youth are detained or incarcerated in adult jails and prisons. Studies show that youth held in adult facilities are 36 times more likely to commit suicide and are at the greatest risk of sexual victimization. Youth of color are over-represented in the ranks of juveniles being referred to adult court. In 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that transferring youth to the adult criminal justice system does not protect the community and substantially increases the likelihood that youth will recidivate.

Improving Aftercare and Reentry Services

The best reentry programs begin while a youth is still confined. Nearly 100,000 youth are released from juvenile justice institutions each year. Most are returned to families struggling with poverty in blighted neighborhoods with high crime rates, few programs, and poorly performing schools. Key to success is connecting youth to people, programs and services that reinforce their rehabilitation and help them become successful and productive adults.

Successful aftercare and reentry programs require coordination between multiple government agencies and nonprofit providers, not only to develop new services, but to help youth better access existing services. Upon release, teenagers must enroll immediately in school or have a job waiting. Otherwise, they are more likely to recidivate…Workforce development—helping teens attain job skills and earn money—is a key motivator for adolescents increasing their commitment to and enthusiasm for learning. Youth must have quick access to mental health and substance abuse services as needed. And they must receive strong support from family and other caring adults.

AFTERCARE SHOULDN’T BE AN AFTER THOUGHT.

FURTHER READING

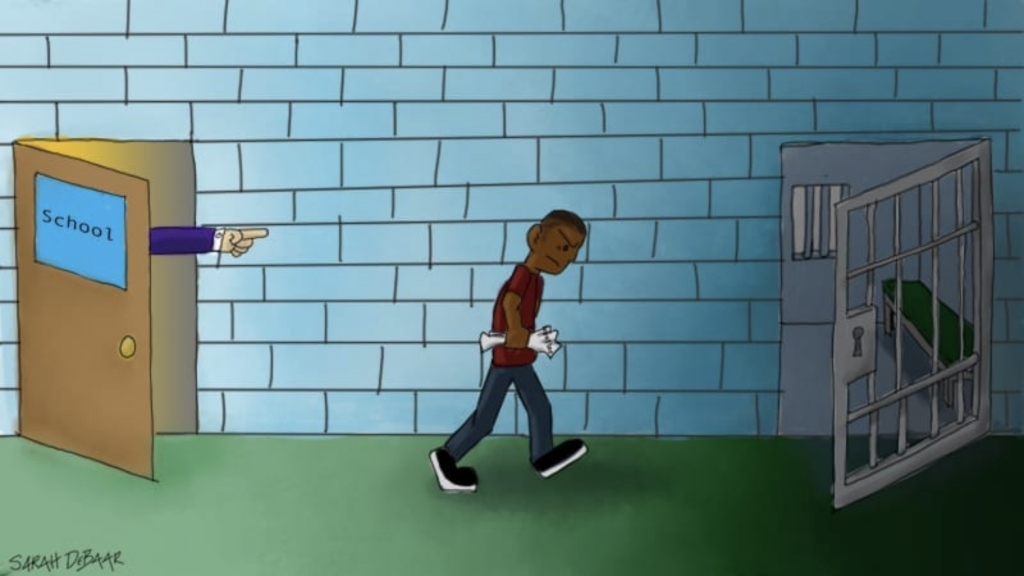

- School-to-Prison Pipeline Infographic

- What is the Prison Industrial Complex? – Tufts University Prison Divestment

- Ending the School-to-Prison Pipeline Starts With Getting Rid of School Suspensions

- Plugging NYC’s School-To-Prison Pipeline