THE CHINESE LADY :: Online Lobby

Welcome to The Chinese Lady Online Lobby experience! Explore additional information below.

Share your personal reflections

The Chinese Lady invites us to witness Afong Moy’s life journey. What reflections do you have on the experiences she shares during the play? How does her experience relate to your own? What do you see? We would love to hear your thoughts and responses to the play, in any format and language you’d like—words, drawings, poetry, photos, etc. Share them on social media (Twitter, Facebook and/or Instagram), and be sure to tag @TimeLineTheatre and use the hashtags #TheChineseLady and #TimeLineTheatre so we can find them!

The Journey of Afong Moy and Atung

Originally from Canton (Guangzhou) province, Afong Moy first arrived in the States in 1834. In The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America, Nancy E. Davis calls our attention to how Afong Moy’s treatment as a Chinese woman varied over time: in the first decade, the public viewed the “orient” as one of exoticism, beauty, dignity, and reverend history; then, with the passage of time, they began to form stereotypical views of the Chinese as backward, arbitrary, undemocratic, and sometimes cruel. Eighteen years later, she was last seen in public in Cleveland, Ohio—demonstrating the “flowery land of tea, small feet, and exaggerated tails (tales)” of “the Celestial Empire.” After 1851, Afong Moy’s life was lost in history.

Before 1834

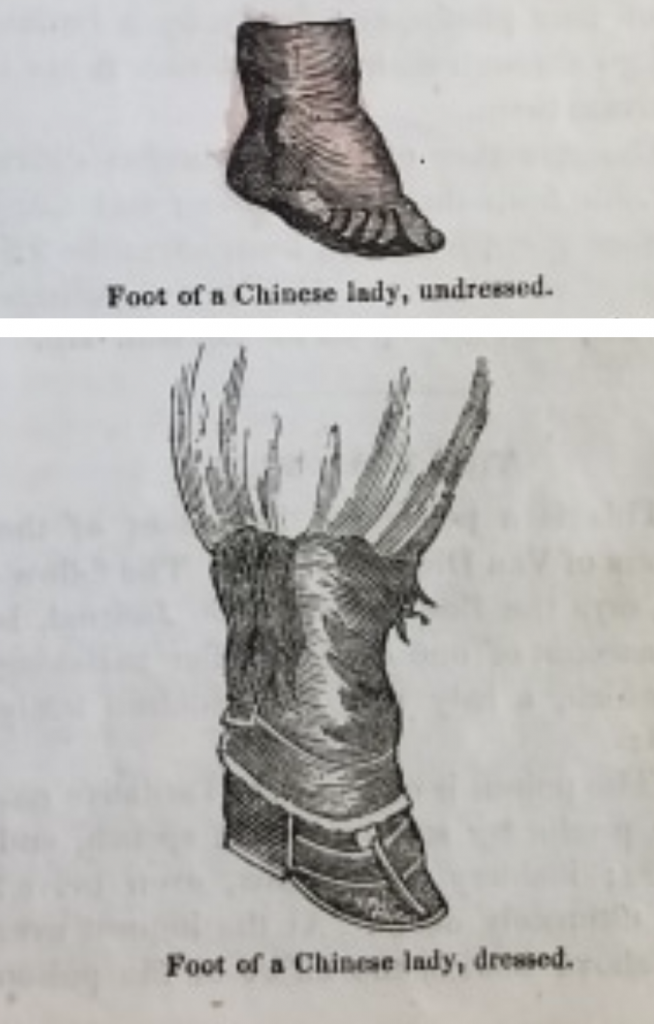

Afong Moy grew up in Guangzhou, China. She was likely born to a middle class merchant’s family, given her bound feet (a custom that was prevalent in middle-upper class) and her family’s contact with foreigners.

It is unclear how Afong Moy was persuaded to take on this journey abroad and become one of the “Chinese curiosities:” some scholars believed that she must have been taken unwittingly; others speculated that Moy was promised an opportunity to travel around the wealthy and mysterious United States.

The First Phase: 1834 – 1837

Nathaniel and Francis Carnes brought Afong Moy to America on a two-year contract, to help market Chinese export goods as exotic. She was promoted as a beauty from an exceptional place, and presented as a “Chinese curiosity.” The Carnes brothers, in particular, highlighted to the public her visual differences—her bound feet, her native clothing, and accessories. In this period, Afong Moy went on tour throughout the mid-Atlantic, New England, the South, Cuba, and up the Mississippi River.

October 17, 1834 — New York, New York

Afong Moy arrived at New York Harbor. New York Daily Advertiser: “The ship Washington, Capt. Obear has brought out a beautiful Chinese Lady, called Julia Foochee ching-chang king, daughter of Hong wang-tzangtzee king. As she will see all who are disposed to pay twenty-five cents. She will no doubt have many admirers.”

November 21, 1834

Martin Van Buren, Andrew Jackson’s vice president, met Afong Moy in New York City soon after she arrived. The next day, Essex Gazette in Massachusetts reported that “the Hon. Martin Van Buren paid his respects to the Chinese Lady yesterday and expressed himself highly pleased with her cast.”

December 1834

Atung was first mentioned in performance ads and newspaper. The performance ads describe Afong Moy as “dressed in the costume of her own country, and surrounded by various articles of Chinese manufacture, worthy of the attention of the curious,” and Atung as “a lad of great intelligence.” Washington Globe, on the other hand, praises Atung as “an excellent cicerone to explain the different curiosities,” whose “animated and elegant features are quite fascinating.

January 1835 — Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Afong Moy and Atung arrived in Philadelphia to start their six-month-long southern tour. At Washington Hall on South Third Street, they received visitors. With the permission of the exhibition manager, eight physicians privately examined Afong Moy’s feet, and published an article titled “Manners and Customs in the East” in Parley’s Magazine.

March 12, 1835 — Washington, D.C.

When Afong Moy and Atung were presented at the Washington Athenaeum, Afong Moy was taken to the Executive Mansion in Washington, D.C., to meet the American President, Andrew Jackson. At the meeting, she questioned “why the Emperor did not sit in the highest seat?” Jackson, on the other hand, asked Afong Moy to “use her powers to persuade her country women to abandon the custom of cramping their feet, so totally in opposition to Nature’s wiser regulations.”

March 21, 1835 — Baltimore, Maryland

Seventeen-year-old Margaret Gibson visited Afong Moy in Baltimore. In her letter to her older brother John, she wrote about her immediate feelings seeing her bound feet: “I had heard so much of her feet being disgusting, that when I did see her, I was much surprised—Could I divest myself of the idea of its being contrary to nature, I should think them beautiful, she placed them very prettily on the ground, and although she totters, and seems pained by walking, I cannot think the appearance disgusting.”

March 28, 1835 — New Orleans, Louisiana

Afong Moy was presented in New Orleans, in the large hall of the North America Hotel, for one week only. In New Orleans, her manager passed out broadsides advertising “The Chinese Lady” and placed them in shop windows to draw a crowd.

April 20, 1835 — Charleston, South Carolina

Afong Moy and Atung were presented in Lege’s Long Room, in Charleston. Several blocks from the Long Room, most of the city’s slave auctions took place at the Exchange Building. She had likely seen such slave markets in Baltimore and Washington.

July 1835 — Boston, Massachusetts

After Afong Moy and Atung finished their Southern tour, they started their New England tour from the Washington Hall on 221 Washington Street, near the Marlboro Chapel where John R. Peters would establish his Chinese Museum in 1845. In Boston, Afong Moy and Atung had also visited certain schools and parties for a day exhibition.

In this tour, after the Boston presentations, Atung’s name was dropped from all the announcements. Around the same time, according to the Boston Commentary, Afong Moy started to take English classes. She was then seen speaking very few words in English in her presentation.

October 1835 — New York

By October 1835, Afong Moy and company moved from town to town, zigzagging from Salem, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; Worcester, Massachusetts; Hartford, Connecticut; New Haven, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersey; Concord, New Hampshire; and up to Albany, New York.

The Second Phase: 1838 – 1851

April 1838 — New Jersey

After Afong Moy’s managers made enough profit off her, they discarded her in New Jersey. The media reported how she was in dire straits, like “a wretch of the worst kind.” After the 1838 press coverage of Afong Moy’s dire situation, the county authorities of Monmouth, New Jersey boarded her in the local poorhouse at public expense.

1838 – 1847

An eight-year interregnum out of the public eye.

In 1842, due to China’s debacle in the First Opium War (1839-1842, see further details below), foreigners started to gain more access to the previously restricted land. Westerners quickly took advantage of the increased access, to capitalize the West’s curiosity of China. China’s failure in the First Opium War also resulted in their disenchantment of the “Far East Celestial Empire,” as they came to realize China’s weak military forces and underdeveloped technological state.

1847 – 1849 — New York City

In 1847, Afong Moy was sold to P.T. Barnum, and became a showpiece at the P.T. Barnum American Museum. By the end of 1849, Barnum replaced Afong Moy with Pwan-Ye-Koo, a younger Chinese Lady who had smaller feet.

February 21, 1851 — Cleveland, Ohio

Afong Moy’s last public appearance was in Cleveland, Ohio, where she was presented in the city’s Empire Hall, demonstrating “the flowery land of tea, small feet, and exaggerated tails (tales)” of “the Celestial Empire.”

From Trade to War: The History behind the Opium Wars

The first Opium War was triggered by the Chinese government’s confiscation and destruction of British merchants’ illegal opium exports.

In 1757, Emperor Qianlong of China adopted a highly restrictive policy regarding the movement of Westerners in China, making the south port of Guangzhou the only port where foreign trade was allowed. Great Britain had been buying increasing quantities of tea from China, but it had few products that China was interested in buying by way of exchange, especially after the Emperor Qianlong’s restrictive policy. In response to the trade deficit, the British merchants, who were in control of India’s foreign trade and with the financing of this trade centered in London, developed a three-way exchange: the tea Britain bought in China was paid for by India’s exports of opium and cotton to China. As the demand for tea rapidly increased in England, British merchants actively fostered the profitable exports of opium and cotton from India. In the year 1820, the opium trade grew dramatically.

As an increasing number of Chinese became addicted to opium, the Chinese government finally decided to confiscate more than 20,000 chests of opium—some 1,400 tons of the drug—that were warehoused at Canton. Three months after the confiscation, the British fleet arrived at the mouth of the Canton River. The Opium War broke off between China and Britain.

In 1842, after losing the war to Britain, China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing, ceding Hong Kong Island to the British, while increasing the number of treaty ports from one to five.

For more information, watch PBS’s documentary The Opium Trade in China.

This video from Vox—entitled “The surprising reason behind Chinatown’s aesthetic” and published in May 2021—served as an inspiration for The Chinese Lady design and dramaturgy teams when creating the scenic design and lobby displays. Watch:

Constructing Chineseness: The History Behind Chinatown

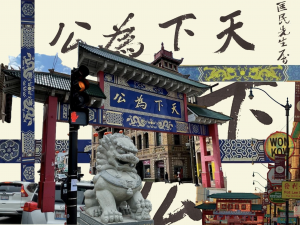

With its teal-colored pagoda roof on top and elaborate ornamentation on the surfaces, the signature dragon gate at Chinatown announces itself as an entrance to an exotic oriental world. Such an iconic sight of Chinese arch can be found in Chinatowns all over the world, but never in an actual Chinese city. In fact, in the very beginning, Chinatown–with its daring colors and shiny hanging lanterns–was specifically designed to cater for the western gaze, not to present an authentic China.

The story started in San Francisco, where the brutally targeted Chinese community invented a strange and exotic Chinatown, in order to protect their land. From the mid-1800s to early 1900, the racist housing policies of the city and the wide-spread hatred toward Chinese men forced the largest Chinese American community to be confined into a 15-square block downtown San Francisco. Then, in 1906, the situation further deteriorated as the city leaders planned to drive out the entire community to the south edge of the city, right after an earthquake had just burnt the neighborhood into ashes. In order to survive, the Chinese leaders proposed transforming Chinatown into a tourist attraction, magnifying its exotic elements to capture the public imagination. They hired American architects, who knew little of Asian architecture beyond stereotypical images of pagodas and temples with massive curved roofs and curled eaves, to build an oriental city. A new structural and decorative vocabulary thus grew from western fantasy: multi-tiered eaves simulating multi-storied pagodas, stone lions guarding the entrance, golden dragons coiling on the street façade. Chinatown then emerged from the earthquake as an “authentic ethnic preserve” filled with racial peculiarities and cultural oddities.

Now, our play, The Chinese Lady, has also adopted some of the familiar Chinatown elements in our set design––such as the hanging lanterns, the blast of colors, and the decorative patterns. But, this time, we invite you to no longer see them as mere spectacles of the others, but to look beyond the façade, and think with us as we enter the story of the first Chinese woman living in the States, Afong Moy.

Not Entirely American, Not Entirely Chinese

— The Aesthetics of Chicago Chinatown

Pui Tak Building — 2216 S. Wentworth Ave.

Designed by Swedish architects Christian Michaelson and Sigurd Rognstad, the Pui Tak Building has been a Chicago landmark since its establishment 1927. Although the architects had little knowledge of authentic Chinese architecture, they drew inspirations from a newly published book by Ernst Boerschmann, a German architect and photographer who had spent several years travelling through China and documenting its buildings and landscapes. Like many Chinatown architecture, the building adopted the element of pagodas on top of its structure. At the same time, the architects also added on the walls decorative tiles that are not Chinese, but American. The titles were made by the Teco Pottery Company in Crystal Lake, right here in the state of Illinois. None of the motifs are truly Chinese but rather designed by a creative American designer who had seen little real Chinese Art or Architecture.

Chinatown Gateway, 1975 — Junction of Cermak Rd. and Wentworth Ave.

Conceived by a group led by George Cheung and designed by Peter Fung, this all-steel gateway was built to celebrate Chinatown’s revival in the 1970s after three decades of sleepiness and commercial decline. To give the gateway a modern look, the designer specifically avoided the use of ornamental details. But, in 2019, when the gateway was renovated, drawings of dragons and floral patterns were added to further adorn the structure. On the front of the gate, the plaque reads, “All under heaven are equal,” in the calligraphy style of the first provisional president of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen. But, the gateway is so adorned that the writings on the plaque become buried in ornamentation, as if they have lost their meanings as words, and become mere decorations.

Nine Dragon Wall, 2004 — Northeast Corner, S. Wentworth Ave. & W. Cermak Rd.

Sponsored by the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, the Chinatown dragon wall is a shortened version of a famous glazed tile wall in Beijing’s Forbidden city. Originally, the Nine Dragon Wall in China was built by the Qianlong Emperor in 1733, to demonstrates the magnificence of the Forbidden City, as well as the pride and honor of the imperial family. In traditional Chinese architecture, what separates the inside of a home and property from the outside and the street is not a gate, but instead, a screen wall. The Nine Dragon Wall was such a screen wall that prevents strangers from the outside to look inside. In the Chinatown context, where the partition is replicated out of context and in a shorter form, the wall becomes a single tourist attraction that invites the visitors to not look away, but to further look into it as an oddity.

Chinatown Square Plaza, 1997 — Archer Ave. between S. Wentworth & Princeton Aves.

This block-long pedestrian mall was designed by American architects Harry Weese & Associates. The plaza now hosts a hodgepodge of gift shops, restaurants, grocery stores, and candy shops. The rather modernistic plaza, on the other side of Archer Avenue, was built as a community gathering place. In that plaza, the bronze zodiac sculptures around the edge were ordered in 1990s from the city of Xiamen, China, whereas the salmon and teal-colored openwork steel pagodas are American in design and manufacture.

Recommended Books & Articles

- Asian America: A Primary Source Reader-Yale University Press, by Cathy J. Schlund-Vials, et al.

- Chinese Women of America, by Judy Yung

- Every Step A Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet, by Dorothy Ko

- Orientalism, by Edward Said

- “Ornamentalism: A Feminist Theory for the Yellow Woman,” by Anne Anlin Cheng

- San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History and Architecture, by Philip Choy

- Surviving on the Gold Mountain: A History of Chinese American Women and their Lives, by Huping Ling

- The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America, by Nancy. E. Davis

- The Making of Asian America, by Erica Lee

- “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans,” by Claire Jean Kim