My parents were born and raised in Detroit. I went to school in the city and grew up in a suburb on its northern border. Though I’ve called Chicago home for the last 26 years, I will always be deeply influenced by my Detroit roots.

But I’m less proud to admit that prior to reading Paradise Blue—which as this post is published is opening in its Midwest premiere at TimeLine—I knew little about a historic part of Detroit’s rich cultural history that had vanished before I was born.

From the 1920s through the ‘50s, the Black Bottom neighborhood was home to a growing population of African Americans—many of whom had migrated from the South to seek employment in the booming auto industry. The neighborhood’s business and entertainment center—Paradise Valley—became an epicenter for music through the ‘40s and ’50s, drawing famous blues, big band, and jazz artists to the numerous black-owned clubs, performing for enthusiastic, mixed-race crowds.

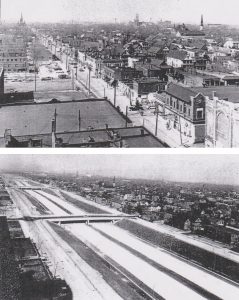

But by the 1960s, Paradise Valley and Black Bottom ceased to exist.

Mayor Albert Cobo and his mostly white city government hatched an urban renewal plan for the Motor City, including the buyout and elimination of Black Bottom to pave the way for their new vision. Gone were the the homes, businesses, music, and culture of Paradise Valley. New were the Chrysler Freeway and, ultimately, Ford Field—the stadium occupied by the NFL’s Detroit Lions.

Thankfully, Dominique Morisseau is helping tell the tale. TimeLine produced her play Sunset Baby a year ago, and we’re honored to present the second production of Paradise Blue, following its recent premiere at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and a year before its planned Off-Broadway debut in 2018.

A passionate native Detroiter, Dominique is crafting an ever-growing body of work that pays homage to her hometown’s history, not unlike what August Wilson did for his beloved Pittsburgh. Her trilogy of Detroit ’67, Skeleton Crew, and Paradise Blue puts the citizens of a great Midwestern city on stage with humanity, humor, poetry, and authenticity.

We couldn’t be more excited to have her vital storytelling at TimeLine again, under the always inspired direction of Company Member Ron OJ Parson. He’s joined by Chicago jazz legend Orbert Davis, lending his renowned artistry to the production by composing and recording original music for Paradise Blue.

These artists will take you back to Paradise Valley, circa 1949, for the beauty of the jazz, the soulfulness of the musicians, the struggles of a neighborhood in transition, and the haunting decisions that would change the landscape of a city.

Bringing this play to our stage now feels apropos, as Chicago continues to see gentrification changing neighborhoods, and economic development flourishing in some, but absent in many, parts of our city.

And a year ago—57 years after this play is set— plans were unveiled in Detroit for a multi-million-dollar development known as the Paradise Valley Cultural and Entertainment District, aiming to highlight African American arts and businesses. It calls for a jazz club, restaurants, boutique hotel and mixed-cost housing. Paradise Valley’s urban renewal, version two. Time will tell if this new vision—and all its good intentions—will have the desired impact.

History can’t be rewritten, but it can be told, with the hope that the future can be bettered. I look forward to the stories that Dominique has yet to write about our beloved hometown and its many tales not yet told.

And in the meantime, I invite you to join us at Blue’s Paradise club for Dominique’s story about an era and a place now vanished. Paradise Blue runs through July 23.