A History of the American Freak Show

This was a marvelous diversion. I’ve always adored carnivals and freak shows. – Atung as Andrew Jackson, The Chinese Lady

While Afong Moy may have been t he first Asian woman to immigrate to the United States, she was far from the first “exotic” body to tour rural America on display. Indeed, after P.T. Barnum popularized the freak show in the mid-19th century, exhibits of “human oddities” continued to enthrall rural Americans for around a century. By understanding the grim history of the freak show, we can understand how American attitudes towards non-White bodies changed throughout the 20th century.

he first Asian woman to immigrate to the United States, she was far from the first “exotic” body to tour rural America on display. Indeed, after P.T. Barnum popularized the freak show in the mid-19th century, exhibits of “human oddities” continued to enthrall rural Americans for around a century. By understanding the grim history of the freak show, we can understand how American attitudes towards non-White bodies changed throughout the 20th century.

The term “freak” broadly encompassed anybody who was considered to be abnormal to American society. However, most people exhibited in American freak shows were either non-White (“exotics”), disabled (“monsters”), or both. By labeling these people as “freak,” the American sideshow marked them as less than human and allowed its audience to look upon the performer as an object.

Non-White and disabled bodies remained the mainstays of the American freak show, but as Western theories of race shifted, so did the marketing of so-called “exotics.” Early shows portrayed non-White bodies as foreign wonders newly discovered by Western explorers. Some of these exhibits even referred to non-White freaks in aggrandizing or flattering terms, describing them as visiting nobility or foreign emissaries. The draw of these foreign bodies was so powerful that White “freaks” were often given exotic backstories to boost their allure. Indeed, one of the most famous sideshow exhibits, the Wild Men of Borneo, featured dwarf brothers Hiram W. and Barney Davis, two Americans of European ancestry.

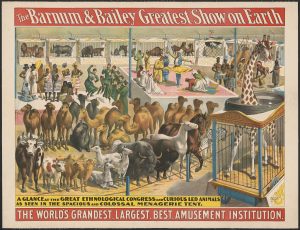

However, after the publication of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in 1959, the nature of the “exotic” sideshow shifted. As pseudoscientific theories began to use evolution to explain physical differences between human races, freak shows began marketing themselves as scientific displays. P.T. Barnum envisioned his 1884 “Grand Ethnological Congress” as an educational exhibit where the “ethnologist” could see “representatives of notable and peculiar tribes.” Always, these theories viewed Whiteness as the mark of being fully evolved. Popular “freaks” were those like Henry Moss, a Black man with patches of white skin, who seemed to be “evolving” before the crowd’s very eyes.

Ironically, while these freak shows sought to prove White supremacy scientifically, for a few performers of color, the status of freak became a rare way to bend the rules of a society that scorned non-White bodies. Chang and Eng Bunker, the original Siamese Twins, used the celebrity and wealth they gained from the freak show business to enter the high society of the antebellum South. Their fame and freak status allowed them to transgress some of the strictest racial boundaries. Despite anti-miscegenation laws, both twins married White women and even purchased slaves. Similarly, billing themselves as Zulu princes, missing links, or African wildmen, several Black Americans made careers of touring the Jim Crow South as “freaks.” These performers made an exaggerated show of racial difference, babbling at audiences in improvised “African” languages and performing feats of “savagery.”

By the mid-20th century, the American sideshow had gone out of vogue due to various social changes. Movies and TV became more popular, replacing the circus as the preferred form of entertainment for the American working class. Meanwhile, social movements championing the rights of minorities made the display of “exotics” increasingly distasteful, and as medicine began to diagnose and explain physical deformities, the “monster” was re-framed as a victim of disease. Rather than approaching disabled bodies with awe, people began to approach them with pity.

The fall of the American freak show emphasizes that “freak” truly is a social construct. As Western society slowly extended its category of “human” to include non-White and disabled people, the 19th-century freak show, which demanded that its audience look upon these people as objects, could no longer survive.

Alisa Boland served as Assistant Dramaturg for TimeLine’s Chicago premiere production of The Chinese Lady.