Before rehearsals for What the Constitution Means to Me began, dramaturg Maren Robinson (MR) sat down with our two experts, Northwestern University history professors Joanna Grisinger (JG) and Kate Masur (KM), to talk a bit more about the Constitution. Read their conversation below.

I appreciate the creativity of what Heidi Schreck was able to do with the play itself by dramatizing the relationship of one woman to the Constitution. It offers a perspective that’s really complicated and that links the Constitution itself and the contours of an individual life.

Maren Robinson: We are so excited to have you at TimeLine. I’m always curious how people end up studying what they study. You are both historians. How did you come to have the Constitution as an area of specialization?

Joanna Grisinger: I was trained as both a lawyer and an American historian, so the Constitution obviously looms pretty large in both sides of that. My work talks about the constitution along with a lot of other laws, and so I try to understand the Constitution’s role in all sorts of rights claims in the 20th century. Some of that has been statutory. Some of it’s been constitutional. I will say, one of the most fun things I get to do is to teach constitutional law to undergraduates, since it looms so large in popular discourse, and students don’t necessarily have a full understanding of what constitutional rights there are. There’s language about the Constitution, and what the Constitution protects, out there in popular discourse, but without any sort of clarity to that. So, in a variety of classes I teach, getting to talk about what the Constitution says, what the Supreme Court has done with the Constitution, and how things change, is one of the most fun kinds of teaching I get to do.

MR: That’s great. Kate, how did you come to it?

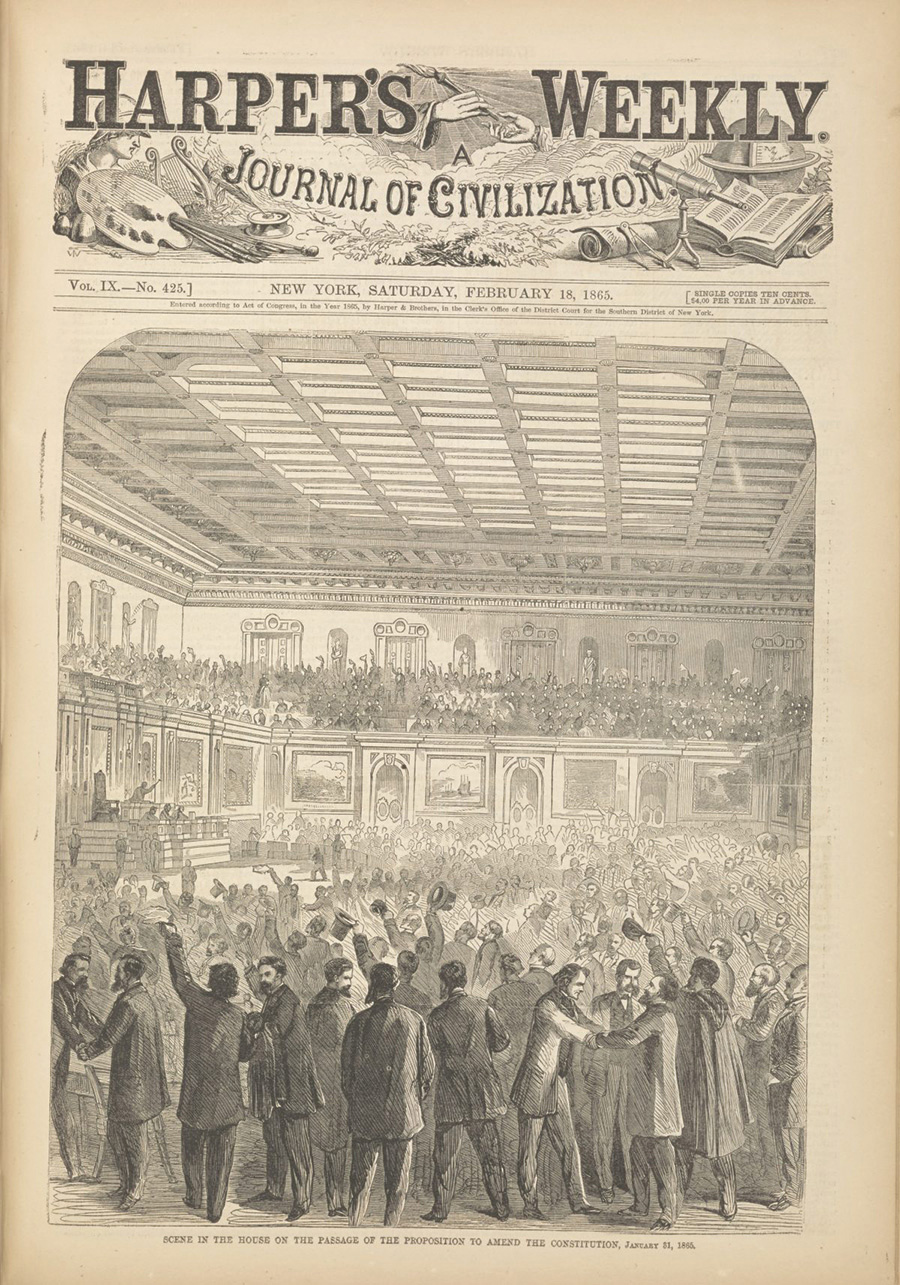

Kate Masur: In college, I got interested in something called critical legal studies, which is a movement of leftist law professors who were interested in law not as separate from society, but as embedded in society. I was lucky enough to find an English professor who had a similar interest and was willing to talk to me about those issues, and I later became a historian who focuses on Reconstruction, a period when the Constitution was dramatically amended. I’ve been very interested in the ways the Constitution was changed during Reconstruction, as well as the new federal statutes passed at that time.

MR: Thank you. I think it’s nice to see the interest coming and going in in many directions, because that’s there in the play, too.

You mentioned teaching, and I’m interested in hearing more. I know you’ve taught courses together and separately on the Constitution and various rights that roll out from it. I would love to hear a little bit more about your teaching experience and the sort of misconceptions you encounter about either the Constitution, or our laws or rights, or the interplay of those things. I’m interested in this sense of embeddedness you describe between rights and the context or the history around them. That they’re not taking place in a bubble.

If there’s anything you’d like to share that you feel comes up all the time when you teach that you wish you could clarify for the general public, I’d love to hear it.

KM: There’s a lot of public discussion about the Constitution that is not necessarily very well connected to how the Supreme Court thinks about the Constitution, and connected to that is a lot of discourse around rights and what Americans think their rights are. People often invoke rights and believe that the original Constitution, from 1789, is the foundation of those rights. Or they look at the Bill of Rights from 1791 and say, “I know my rights are listed in the Bill of Rights, let’s look at those. Those are my rights.”

There’s a bit of a misconception here, because in early U.S. history, the general consensus was you could only really invoke those rights against the federal government, not against the states. The framers of the Constitution feared that a strong central government might infringe on individual rights; they felt that state or local governments were not so threatening.

The idea that the U.S. government should protect people against violations by local and state officials really only entered the Constitution in the 1860s with the Reconstruction amendments.

To the extent that we believe we have certain rights that no government entity should be able to violate, that is not a late-18th-century idea. That is a post-Civil War idea. If you start to think about it that way, you have to do things like question the original framers—the guys with white wigs on. And you have to think about the ways that the project of ending slavery actually created rights for everyone.

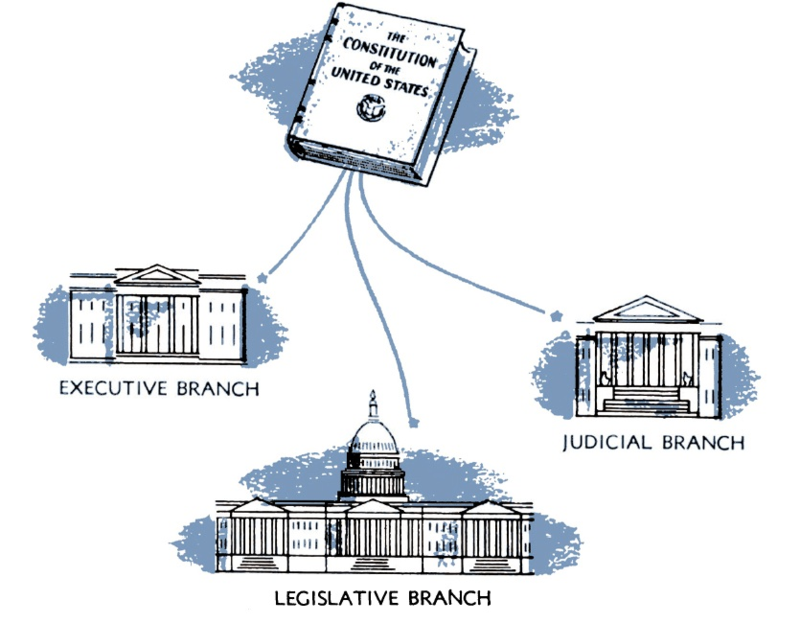

JG: Something that is important to know is that the Constitution only applies against the government. That is, there’s a doctrine of state action: the Constitution, the language of the Constitution, almost every part of it only restricts government actors, state actors. The State of Illinois cannot interfere with your freedom of speech, but Facebook can, TimeLine Theatre can. Any sort of private institution is not subject to the Constitution’s limitations. And so one of the first things to note, if you feel like your rights are being infringed upon, is to understand who’s actually doing it.

JG: So that’s just one clarifying question that undergirds constitutional law. Another one is that it’s too easy to think about the Constitution as the end all and be all of the source of laws; whereas, the Constitution is a floor, not a ceiling, in most cases. It’s not a cap on the things government can do.

There’s a whole world of state constitutions that provide rights above and beyond what the federal Constitution does. And we’re seeing those get increasing prominence right now as state Supreme Courts are reading state constitutions to provide protections for abortion and reproductive rights above and beyond what the Supreme Court has said the Fourteenth Amendment means in Dobbs [v. Jackson]. There’s all manner of Federal and State laws that certainly limit what Facebook can do, that limit what TimeLine Theatre can do, that limit what we, as instructors at a private university, can do, etc., that have little relationship to the Constitution.

And so too much of a focus on the Constitution tends to affect our imagination, both of what else might be out there, and what else might be possible, because it is a pretty brief document. But there’s a lot of other laws out there.

The last thing I would say is that we tend to forget that the Supreme Court has been a “small c” conservative institution for almost its entire history. The period from the 1950s through the 1970s, when the Supreme Court was a little bit more at the forefront of pushing for things like racial integration, pushing for women’s rights, pushing against laws that infringed on reproductive autonomy, that infringed on women’s rights, etc., is really an outlier in terms of how the Supreme Court has operated for most of American history. So, the idea that we would look to it for progressive change during a pretty limited period of time has affected our imagination about what the Supreme Court can and can’t do.

MR: Building off this in a strange way, I think what’s so unique to me about the play is that Heidi has this very personal relationship with the Constitution from a very early age, and she has a real, genuine affection for the Constitution and the government. Then critique comes in, especially as her character ages. How do these feelings of critique and appreciation jostle for the two of you?

JG: The law, Constitution, the Supreme Court decisions, they’re just words that have to be given meaning. So every generation, every new decision, is an opportunity for courts to give meaning to legal language, and for people to press before the Supreme Court different ideas of what this language can mean. And so there’s real opportunity there, and a lot of the play is about not just the Constitution itself, but the possibility of giving these words new and different meaning. The form of judicial decision making we have means that we’re constantly negotiating what this language means.

That said, the precedential nature of judicial decision making, and the fact that constitutional law isn’t just the actual words in the Constitution, but also all of the Supreme Court decisions interpreting what the Constitution says, means that the words and the decisions of straight white men, and their interpretations of the Constitution across time, and the way they’ve read previous decisions, and their inability to see people of color, or white women, or LGBTQ folk, or others as fully rights-bearing individuals who deserve the same kind of protection, continues to bind us today.

And so, we’re not really starting from scratch with every single Supreme Court decision; each case battles with the way these things have been done in the past.

KM: I think one of the things that’s really cool about the play is that Heidi starts out really loving the Constitution and talking about it as a kind of amazing magical document. That sense might echo the kind of patriotic education that many of us received in public school. I don’t know if it’s still true, but when I was growing up, we said the pledge of allegiance to the flag every morning in most grades in elementary school. We were supposed to put our hand over our heart and face the flag and say it every morning.

And then, as the story goes, Heidi becomes more critical. She thinks about her story, and in a way the play is like a dialogue between the story of her life and her family’s life, particularly the women in her family, and her reflections back on the Constitution. I think that might mirror the feeling many of have that we invest in our culture as children, and then as we grow up, we come to reflect on the shortcomings of the ideas we received, or on the ways those ideas don’t actually cover our experiences.

I feel the same way as Joanna in the sense that I don’t really have affection for the Constitution. I do feel frustrated by the Constitution. But mainly I feel like it is what it is, and it’s a thing that is very important to our culture. It’s not just important in the literal legal sense but also because it’s an object that, broadly speaking, our culture venerates, and it’s a source of the idea of American exceptionalism.

Americans tend to boast that our constitution is more long lasting than everyone else’s constitution. It is somehow better than other countries’ constitutions. It’s more stable; it’s more ingenious. And that connects to the patriotic ideas that so many of us learn in school and, again, that many of us grow up to kind of reevaluate and think about in more complex ways.

MR: What you’ve said dovetails nicely with the research I’ve been doing of old film strips about the Constitution from the 1950s and ’60s and ‘70s, some of which I think will be running in our lobby. There’s this sort of deep, patriotic underpinnings with flags, and music that’s swelling behind them, and there is very much this idea of American exceptionalism. It’s a nice thing to remember that we sort of accept these things as given. We receive them in a certain way as we’re educated.

I also love what you’ve both said about the disconnect between what people think their rights are, and what they actually are. One of the things that we talked about in a production meeting and is a concept in the play is the idea of affirmative rights and negative rights. Could you share a definition of those, and also talk about the fragility of those rights and what our perception of personal human rights should be in the context of State or Federal laws?

KM: If we think about the promises of rights in the Constitution, those rights are mostly framed in negative terms. That is to say—rights are discussed as what the state cannot do to you, rather than what you have a right to. For instance, the State cannot directly, in most cases, tell you that you can’t talk about certain things; the State cannot deprive you of certain kinds of due process. It’s basically promising an individual person protection against certain kinds of incursions or coercions by the State.

But it’s not saying you affirmatively have a right—let’s say, to something like health care, or to a basic standard of living, or to terminate a pregnancy at certain times in that pregnancy. There is not even an affirmative right to travel across state lines. This has come up recently because of the Dobbs decision. The right to travel isn’t literally mentioned in the Constitution, but courts have understood the Constitution to imply that the government can’t stop people from crossing state lines.

So, our rights tend to be framed as negative in the sense that it’s what the State cannot do to you, as opposed to affirmative positive rights in the sense of what we’re entitled to.

JG: There are also some institutional limitations. Courts are in some ways fairly weak entities. They can say things, and we comply with their decisions because of the legitimacy courts have. But say a court orders a public school district to maintain a certain level of education. What if the legislature—which, unlike a court, does have authority over spending—says, “No, we’re not going to fund that.” What if they a court says, “Yes, there is an affirmative right to health care.” Well, there now need to be budgeting decisions that come from the legislature. Much of the constitutional rights are framed in the negative, but courts are also very loath to go beyond that, to demand certain kinds of changes that they don’t necessarily have the power to implement.

You get into some thorny institutional questions very quickly. The way that the system has been set up around negative rights, makes it very hard to pursue affirmative rights.

Another example is the right to vote. We talk about a right to vote as if there is an affirmative right to vote in the Constitution, but it is not there. There are certain amendments that say the right to vote cannot be denied on the basis of race, sex, or age. That leaves a lot of other reasons that the State can deny you access to the vote.

It gets back to this question of the way we talk about certain kinds of rights versus how they are actually framed in the Constitution. The Supreme Court will even talk about a right to vote while not suggesting that there is an affirmative right to vote. That framing has been very problematic for people who are seeking to make sure everybody can vote, and there are at least a couple of groups seeking a constitutional amendment that would state an affirmative right to vote, which would force the courts into a different posture around those cases.

MR: You mentioned the court’s lack of willingness to extend certain things when they perceive that it’s going to need a legislature to enact it or pass a budget. Would you say that about the Supreme Court? We’ve talked about a moment when it seemed to be expanding rights. Now, with the appointment of recent judges and the overturn of Roe v. Wade, it’s made the general public more aware about the Supreme Court and all the decisions that are being made in State courts leading up to cases that make it to the Supreme Court.

JG: Constitutional law has to be given meaning, and it’s inevitably a human process to do so. And we want to be careful of valorizing the Supreme Court too much, and assuming that decisions that come down from the Court are correct. As opposed to acknowledging that the Court’s decisions have legal authority. We don’t necessarily need to adopt that version of what the Constitution means, in terms of our imagination about how the world, how America, should look, or what kind of rights we should or shouldn’t have.

I think it gets a little too easy to think of the Supreme Court as having some sort of additional insight into what the Constitution means—as opposed to being this group of nine people whose decisions about what it means bind us politically and legally. But that doesn’t mean we have to accept their assumptions about how the world works, and how they got there.

We need to be thinking about what is possible, what could happen in the future, what we might do with the Constitution in the future, how to approach overturning past decisions that we don’t like, how to protect decisions that you do like, etc. To think about the Supreme Court as a political branch that simply has different legal and professional constraints than other branches do, but not give it too much magical power.

KM: I would just add that the historical moment that we’re living in right now—the conservative majority on the court, which was consolidated during Donald Trump’s presidency—is the result of a very organized conservative legal movement.

To add on to what Joanna said, the court is another political branch among the three branches of our government. This court is the result of social movement organizing and a huge amount of financing that has created a cadre of very conservative judges, who are conservative in a variety of different ways. The movement has, in an organized way, sought to position those judges for appointments on the federal bench at all levels, and has also sought to get Republicans elected to the presidency and to the Senate, which confirms federal judges.

We should just be aware that the courts are subject to the same kinds of pressures of politics and money and movement organization that other branches of government are. Yet unlike authorities in other branches of government, these people are appointed for life. Once they’re there, it’s not very easy to get rid of them. Overall, though, we need to think about the Supreme Court as being very much of this world and very much about power in politics. It’s not that these are just are a bunch of really smart people who have somehow magically found their way to the top of our federal court system.

MR: That dovetails nicely with my next question. I think that there can be a sort of stagnation in the population around thinking about how to change government, particularly when you have, say, a judiciary where they’re going to be in power for the rest of their life. It’s giving these institutions that sort of magical power—the public now has to wait until someone dies for things to change. Or we’re giving power away to the organized movements or PACs that have money.

How does an individual insert themselves in this process? How do they become active and motivated to try and effect change when they are frustrated with the laws, or the decisions that are being handed down by various governments that are impacting their individual lives? What suggestions do you have?

KM: I think one of the themes of this conversation is the Supreme Court is powerful, but it’s not the only thing that’s powerful. The recipe for being involved in change is the same as it always has been, which is to get involved in the kinds of organizations that are kind of doing the kinds of work that you want to see done. One of the things that lawyers and legally oriented organizations do, or that any organizations do with the advice of lawyers, is find creative workarounds to grapple with whatever situation you’re being handed.

I’m thinking about issues related to the environment and environmental regulation, where many of us would like to see stronger curbs on fossil fuels and things like that—things that the court is likely not going to accept even as warnings about catastrophic climate change are getting more and more dire every time we open the newspaper. But there are many other ways of working on that issue. Just because the court is not aligned with people who understand what’s going on with the climate doesn’t mean that there aren’t other ways of working on the issue.

So I would say that we shouldn’t be paralyzed by what the court is doing. I mean absolutely not—the opposite. It should galvanize people to do more, to find the workarounds that many organizations and many people are already involved in, and join forces.

JG: If you’re not a lawyer, if you’re not involved in Supreme Court litigation, there are groups out there who are trying to amend the Constitution in various ways. But that requires a lot of political activism for a cause, getting a lot of signatures, etc. If that’s something people are interested in doing, simply do an online search for “Second Amendment,” “Constitutional amendment,” “voting rights,” etc. You can find those groups. There are so many places to push outside the court.

In terms of State and Federal law, it’s very easy to figure out who your State representative is; start getting in conversation with them. So much of our lives happen at the state and local level, and there are just fewer people, and it’s easier to get involved there as well.

Don’t forget that what happens outside the court can also change the political context the court is operating in. It’s worth noting that before Obergefell [v. Hodges], protection for marriage equality came from a lot of grassroots pushing at the local level, changing the political context that led the Supreme Court to decide the way it did. Now there’s a lot of political pushing in the other direction as well. And so those conversations are very important, even if you’re not a Supreme Court litigator.

MR: There’s one concept I want to mention that comes up almost at the top of the play. Heidi discusses this idea of “penumbra,” which she describes as, she’s on stage, and the lights are on, and there’s this shadowy edge, and then there’s the audience and darkness. And she says, the penumbra is the shadowy edge. Then when we were in in an early production meeting, one of you mentioned that this beautiful sort of metaphor on our stage has actual legal context and meaning. I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about the legal history of penumbra.

JG: In Griswold [v. Connecticut], Justice William O. Douglas uses the term penumbra to describe how things that are not specifically referenced in the Constitution are nonetheless protected by the Constitution—that is, that the Constitution protects a larger category of items, a larger group of things, than the specific words in the text.

Among those he mentions is freedom of association, which is a very important right that the Supreme Court has found to exist in the First Amendment, even though it’s not mentioned in the First Amendment, because the ability to associate with one another is so crucial to the other rights described in the First Amendment like speech, that it is within the penumbra of things that are protected.

The right to travel is not specifically mentioned in the Constitution, but the Supreme Court has agreed that it is within this broader collection of things that is to be protected. The word marriage isn’t in the Constitution, but nonetheless marriage is seen within these protections.

So when we’re talking about liberty, when we’re talking about speech in the broadest terms, we’re also talking about these particular things. To give this broad language meaning, you have to be a little bit more specific about what’s included in freedom of speech, freedom of assembly. It includes a lot of other things.

“Penumbra” is a distinct word for describing the fairly uncontroversial idea that a lot of specific things are protected within the very broad language of the Constitution.

Then the fight simply becomes “well, which are the things that are within that right, and which are the things outside of it.” And I think almost everyone would agree that there are specific rights protected by the Constitution where the words are not actually mentioned in the Constitution. It just becomes a disagreement about which those are.

A lot of conservative lawyers are pushing for a “freedom of contract” that’s protected by the Constitution. But that language isn’t in there either. The idea that the Constitution has this broader meaning that is left up to the Supreme Court to decides actually a pretty uncontroversial one. Instead, it really is a battle over what things are within and what things are without.

KM: Jumping off that, as Joanna said, the term penumbra most famously appears in the 1965 case, Griswold v. Connecticut, which was a case about birth control. It was about whether the State of Connecticut could outlaw the sale of birth control to married couples. The Supreme Court held that no, the State cannot ban the sale of birth control to married couples, and that within a marriage, the ability to make a decision to not get pregnant was protected by the Constitution under the theory of privacy. That privacy within marraige was part of the “penumbra” of rights that were not specifically referenced in the Constitution, yet often affirmed by the court. So Justice Douglas used the term “penumbra” to envelop, as Joanna was saying, the court’s longstanding understanding that the Constitution protected a variety of rights that might not be explicitly named in the actual document.

The thing that I would add here is that people who don’t like the string of decisions that have to do with the constitutional right to privacy regularly ridicule the use of the term “penumbra” in Griswold and also some of the language around it, including where the court, alluding to the line of cases that found that the Constitution protects rights that aren’t explicitly named, writes: “The foregoing cases suggest that specific guarantees and the Bill of Rights have penumbras formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” Certain conservative lawyers and judges ridicule the notion of “penumbras formed by emanations.” It’s the most ridiculous thing they’ve ever heard; they say it’s an example of a judge just making stuff up, of really finding within the Constitution things that aren’t there.

I think the language is vulnerable to ridicule in part because the case has to do with women and sexuality. The idea of a constitutional right to privacy is not that different from many other constitutional interpretations the court offered prior to 1965, regarding a lot of different issues. But because the case is related to women and sex, I think the decision is especially susceptible to being discredited and to people acting like it came out of nowhere.

The court brought the idea of a right to privacy into the Roe v. Wade decision. And it’s one of the things the court criticized in the Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe last spring: that if there is a constitutional right to privacy, it does not include the right to decide to end a pregnancy.

MR: That’s a great answer.

Kate, you’ve been called in to share your expertise on a play before, and Joanna, this is the first time. We’re early in the production process so we haven’t all been in the rehearsal room together to get to see what happens when suddenly other people are saying the words and becoming Heidi. I wonder if there’s anything that has struck you about the process, or what it means to see these things that you work on in a certain way expressed in this artistic way.

KM: I love seeing how theatre can bring ideas and history into a multi-dimensional context, and how—unlike what I usually do professionally, which is trying to provide as realistic and as factual a version of history as possible—theatrical productions, and playwrights, have greater license. Plays can be fiction or fictionalized, and I think that allows you to do things that we can’t do. So I appreciate the creativity of what Heidi Schreck was able to do with the play itself by dramatizing the relationship of one woman to the Constitution. It offers a perspective that’s really complicated and that links the Constitution itself and the contours of an individual life. As TimeLine brings the play to life, you make your own set of decisions about how to represent the play and how to stage it. It provides so many opportunities for creativity that it’s really fun.

JG: I’m fascinated, given that we spend so much time thinking about how to relay stories in an engaging but also specific way in the classroom and in our own writing. It’s also been really enjoyable, given how specifically this play is based in specific constitutional doctrines, and how accurately it has represented what the Supreme Court has said here, what the constitutional language is, while making that a really compelling production. It’s not playing fast and loose with the constitutional language, or with law, in a way that I think would be really easy to do. It’s been really fun to see how the play reads on paper, and I’m looking forward to seeing it in person.

What the Constitution Means to Me begins performances May 10, 2023 and runs through July 2, 2023 at TimeLine Theatre. Learn more and get your tickets now.